Jamaica Gareth Henry: 'I saw my friends killed …

-

There's no safe place in this country'

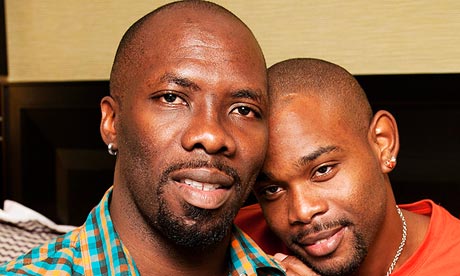

'I was with J-Flag for four years,' says Gareth Henry (left, with his Canadian husband, Aron Charles-Henry). 'During that time 13 of my friends were killed.'

Gareth Henry hit the international headlines in his native Jamaica four years ago when he was beaten by policemen in front of a mob of 200 people who cornered him in a Kingston pharmacy.

A year later, in 2008, the head of the Jamaica Forum for Lesbians, All Sexuals and Gays (J-Flag), fled to Canada following a series of death threats. He was granted asylum.

The 35-year-old gay rights activist and social worker is now one of two co-petitioners bringing the legal challenge against his former homeland at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

"I was with J-Flag for four years," Henry explained on a trip to London this month. "During that time 13 of my friends were killed." He identified several of the bodies. "I took on the leadership of the organisation after the former leader, Brian Williamson, was stabbed to death in a homophobic attack in 2004."

On three occasions, Henry said, he suffered violence at the hands of police officers. The most notorious incident was on Valentine's Day, 2007, when a group of gay men were chased into the Monarch pharmacy in Kingston by a large mob. Henry was with them.

According to his statement to the commission, the police were called but were abusive when they arrived. One officer asked if he was a "batty man" and then all four policemen began beating him with their guns.

He subsequently complained to the Jamaican ministry of justice. "I met politicians and officials. I expressed concern about my safety and the fact that I was being targeted by the police. They didn't respond. The harassment from the police increased," he said.

"When I woke up on the morning there would be a police officer outside my window, saying they were going to kill me. I used to help house gay men who were homeless – primarily because family members had turned their backs on them. Some of these people were dying from HIV/Aids.

"If you are homeless and have no family support and are dying from HIV you have a sense of hopelessness. Even these people became a target for attacks.

"We documented the threats on my life. After the incident in February 2007, that made international headlines, we thought that would make some changes. But I had to go and live in hiding.

"I was stopped in traffic and a police officer said 'I have found you and we are going to kill you'. That statement still lives with me today. When I saw my friends being killed, I always asked 'Am I going to be next?'

"When he said that to me, I suddenly realised I was the next target. So I had to make a decision between running away and trying to find a safe place in a foreign land or staying and being killed.

"I was able to get out just in time but there are many other young men who are faced with the same threats and are not able to leave home and find a safe haven.

"Now I want to hold the Jamaican government accountable. A large proportion of the gay community in Jamaica is homeless and living in poverty and being ravished by HIV. Living with no hope and facing humiliation.

"Those people go through each day trying to survive, being anxious about homophobia and wondering whether they will be the next victim. There's no safe place in this country. We have exhausted all the possible options in terms of negotiations and meetings with the police.

"Why would a sane person chose to be a homosexual? Why would you chose death over life? It's clearly a human rights violation and it's time for radical action. We are calling on the international community to help save the gay community in Kingston."

-

Gay Jamaicans launch legal action over island's homophobic laws

Landmark case seeks to abolish colonial-era 'buggery' laws and stop murders and violent attacks on Caribbean homosexuals

Two gay Jamaicans have launched a legal challenge to colonial-era laws, which in effect criminalise homosexuality, on the grounds that they are unconstitutional and promote homophobia throughout the Caribbean.

The landmark action, supported by the UK-based Human Dignity Trust, is aimed at removing three clauses of the island's Offences Against Persons Act of 1864, commonly known as the "buggery" laws.

The battle over the legislation – blamed by critics for perpetuating a popular culture of hatred for "batty boys", as gay men are derided in some dancehall music – has also drawn a British lawyer into the debate, who said that Jamaica should not follow the legislative example of the UK.

The legal challenge is being taken to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which is modelled on the European Court of Human Rights. Jamaica is not a full member and any ruling would only be advisory and not binding; it would, nonetheless, send out a strong signal of international disapproval.

When the Jamaican prime minister, Portia Simpson Miller, was elected last December, she said she would hire a gay person to serve in her cabinet and condemned discrimination. Despite early sympathetic signals, her government has not attempted to repeal the laws.

The Offences Against Persons Act does not formally ban homosexuality but clause 76 provides for up to 10 years' imprisonment, with or without hard labour, for anyone convicted of the "abominable crime of buggery committed either with mankind or any animal". Two further clauses outlaw attempted buggery and gross indecency between two men.

Jamaica has one of the highest murder rates in the world. Murders of gay men are increasing, according to Dane Lewis, executive director of the Jamaica Forum of Lesbians, All-Sexuals and Gays (J-Flag), who is one of those petitioning the commission.

"This year alone there have been nine [murders]," he said. "The violence in Jamaica is having a spillover effect on other parts of the Caribbean: St Lucia now has a murder or so every year."

One prominent victim was John Terry, the British honorary consul in Montego Bay, who was found dead in 2009 having been beaten and strangled. A note left on his body read: "This is what will happen to all gays."

Many gay Jamaicans have fled abroad, some to the UK. In 2002, two gay Jamaican men were granted asylum in the UK because their lives were in danger from "severe homophobia" in the Caribbean.

Senior Jamaican police officers have in the past dismissed killings as the result of gay-on-gay "crimes of passion" – an interpretation disputed by civil rights groups.

In a House of Lords debate this week on the treatment of homosexual men and women in the developing world, the Conservative Lord Lexden said a "wave of persecution and violence has been suffered by gay people connected with [J-Flag]". Intolerance of homosexuality, he noted, was a legacy of the British empire: "Today, 42 of the 54 nations of the Commonwealth criminalise same-sex relations."

Jonathan Cooper, a London barrister who is the chief executive of the Human Dignity Trust, said: "We want to ensure that Jamaica satisfies its international human rights treaty obligations. We are supporting J-Flag in this case.

"These, and two accompanying cases supported by Aids-Free World, are the first cases before the Inter-American Commission but the issue is clear in international human rights law."

The UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Jamaica is a signatory, protects private adult, consensual sexual activity.

J-Flag has also received free pro-bono advice from the UK City law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in drawing up their legal challenge.

One of the main bodies arguing to preserve the Offences Against Person Act is the Lawyers' Christian Fellowship in Jamaica (which has no connection to the UK Lawyers' Christian Fellowship).

Paul Diamond, a British barrister and Evangelical Christian who specialises in religious discrimination cases, took part in a debate on Jamaica's laws at the University of the West Indies last December.

"[Jamaicans] feel they are being pressurised by the UK and US governments in terms of visas and aid grants to modify their position [on homosexuality], which they say is morally based," Diamond told the Guardian. "I told them that England has totally failed in finding any balance between religious [and civil] freedoms."

The prime minister's office in Jamaica did not respond to enquiries.

Anti-gay laws in the CaribbeanWhile Jamaica holds the crown for being the worst place in the Americas to be gay, the rest of the English-speaking Caribbean has a long history of homophobia. The British colonial administration entrenched "buggery laws" in its colonies, many of which remain in some form.

The Bahamas criminalises same-sex activity between adults in public, although not in private. Jamaican, Guyanese and Grenadian laws do not mention lesbianism, but Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Antigua and St Lucia prohibit all acts of homosexuality.

Trinidad and Tobago's state-sponsored homophobia extends further through immigration laws prohibiting "prostitutes, homosexuals or persons living on the earnings of prostitutes or homosexuals, or persons reasonably suspected as coming to Trinidad and Tobago for these or any other immoral purposes" from entering the country.

Although the law is not enforced, there were attempts from Christian groups to prevent Elton John headlining the Tobago Jazz Festival in 2007. Church leaders were worried about the singer's potential influence on the "impressionable minds" of the island's young people.

Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the Turks and Caicos islands were forced to repeal their sodomy laws in 2000, when Britain issued an order to its overseas territories, which it had to do to meet international treaty obligations.